Pierre August Renoir was born in 1841 in Limoges, France. The town of Limoges was the center of the famous hand-painted porcelain works. Renoir’s parents were members of an active artist and artisan community. His father was a tailor and his mother a seamstress. The family moved to Paris in 1845, and they lived near the Louvre. At age 15, Renoir served as an apprentice at the Paris Limoges Factory, earning enough money to help his parents buy their house. His initial training as an artist required mastery of intricate brushwork, attention to detail, use of rich colors, and a love of flowers.

In 1862, he attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he became great friends with fellow students Sisley, Bazille, and Monet. Chaffing from the realism of the classic style, they searched for new techniques and subjects. They began in 1864 to work outdoors in the Forest of Fontainebleau. Discoveries about the effects of light on subjects from the development of photography spurred the artists to create what became their signature style: Impressionism.

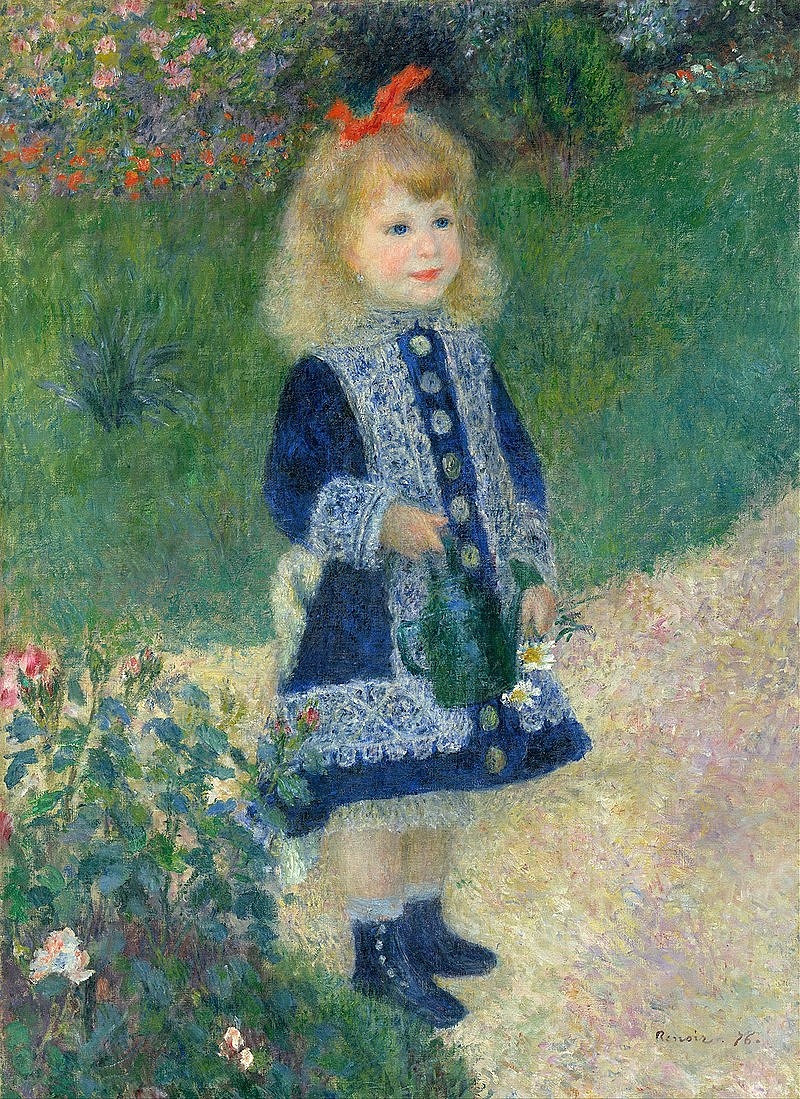

“A Girl with a Watering Can” (1876)

In 1876 Renoir began to paint figure subjects along with landscape and flower paintings. “A Girl with a Watering Can” (1876) (39”x29’’) (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) is a portrait of a young girl who lived in his neighborhood. It illustrates Renoir’s fully developed Impressionist style along with lessons learned from porcelain painting. The charming, young girl is enjoying the sunny day. She holds a green watering can and two daisies. Her eyes are blue and her cheeks rosy. Her elegant blue dress is decorated with wide white bands that look like lace, the type of detail Renoir painted in Limoges. Her outfit is completed with a pair of matching blue shoes. The tops of her white stockings call attention to her lacey bloomers. Renoir used the color red to guide the viewer’s eye through the composition: red roses in the front, red lips, and red flowers in the background. The red bow in her hair draws the eye from left to right, to the group of red flowers behind her and the one red flower in the distance to her left.

Renoir used color dots of yellow, purple, red, pink, and blue, visible only up close, to portray the beige path that runs diagonally across the painting. He painted the lawn vibrant green, blue, and yellow, using visible but subtle brushstrokes. He used broader brush strokes to portray the leaves and flower petals of the plants in the foreground. In contrast, his brushwork on the flowers behind the girl does not attempt to create an individual flower or leaf.

Renoir’s paintings of people are appealing. They also fulfill his desire to create a complex work of art.

“La Promenade” (1876)

“La Promenade” (1876) (67”x43”) (Frick Museum, New York City) is a winter scene in a city park. The focus is on two young blond girls, who look as if they could be twins, and their older sister. All are dressed in winter clothing. The eldest wears a blue velvet jacket with fur trimmed sleeves. The younger girls wear matching blue-green outfits trimmed with fur. One has a fur muff and the other carries a doll. Hats of flowers and fur are perched on their heads. White hose and leather boots complete their outfits. Beyond them on the path, eleven other people are suggested. Two black and white shapes on the path suggest playful dogs.

Renoir grew up with a tailor and a seamstress as parents, and he fell in love and married a dressmaker. His paintings show an unusual amount of knowledge of and interest in depicting the fashion of the time. “La Promenade” was in the second Impressionist Exhibition in 1876. Although the work did not receive much notice at that time, Renoir’s ability to present fashionable and delightful women and children eventually brought him international fame.

“Children’s Afternoon at Wargemont” (1884)

As a result of his earlier successes, Renoir gained patrons and friends from the new professional class. Paul Bernard, a banker and diplomat, became a friend and patron in 1879. “Children’s Afternoon at Wargemont” was one of his many paintings Bernard and his wife commissioned. The setting is the Chateau de Wargemont in Normandy, the Bernard’s second home outside Paris. In the painting the Bernard daughters Marguerite, Lucie, and Marthe enjoy a pleasant afternoon.

Renoir made several trips to Algeria and Italy beginning in 1881. On the trips to Italy, he studied the paintings of Raphael, Rubens, and the Rococo artists Boucher and Fragonard. Their work influenced Renoir to alter his style, and he entered what art historians call his “classical” period. “Children’s Afternoon at Wargemont” (1884) (50”x68”) is still full of bright sunlight, and the theme of a peaceful family day continues. Gone are the suggestive and flowing brushstrokes. They are replaced with precise details in clothing, furniture, wood floor, carpet and curtain patterns, wall paneling, and a pot of flowers.

The two girls are dressed in the fashion of the time and in accord with their ages. The girl in the blue and white sailor dress holds onto her doll, and her eyes directly engage the viewer. Her sister is sewing, and her other sister, slouched on the nearby couch, reads a book. Renoir created a composition of blues and oranges, complementary colors, and complex designs.

“Gabrielle Renard and Infant Son Jean” (1895)

Renoir suffered from arthritis beginning in 1881, and the disease became increasingly debilitating. He had the first attack of rheumatism in 1894. Renoir had married Aline Charigot, a seamstress and model he met in 1880. They had three sons, Pierre (1885), Jean (1894) and Claude (1901). “Gabrielle Renard and Infant Son Jean” (1895) (26”x21”) depicts Gabrielle, Aline’s cousin, who moved to the Renoir home in Montmartre at age 16 to act as Jean’s nanny. She often modeled for Renoir, and she helped him to paint when his hands became crippled by placing the brushes between his fingers. Renoir never stopped painting, but in his later works he necessarily returned to looser brush work. His love of his family is evident in this work and many others.

“The Artist’s Family” (1896)

“The Artist’s Family” (1896) (68”x54”) is Renoir’s largest portrait with life-size figures. The setting is the garden of the family home, Château des Brouillards in Montmartre, where the family moved in 1890. Aline stands at the center with their eleven-year-old son Pierre, standing next to her. Aline’s hat is a remarkable fashion creation of the time, and a red coat with a fur collar are draped over her arm. Pierre leans in affectionately, holding onto his mother’s arm.

Gabrielle kneels down to support young Jean as he stands for the painting. Jean’s elaborate white bonnet and dress are certainly fashionable. The composition of the family forms a triangle that Renoir creates with Aline’s light hat and blouse at the top, the sailor suit and black skirt in the middle, and the white clothing of Jean and Garbielle at the bottom. The protruding edge of Gabrielle’s black skirt anchors the triangle. Necessary to balance the composition is the young girl in red, one of the neighbor’s children. Her red dress and pose, direct the viewer’s eye to Aline. The black sash on her dress and the black ribbon on her hat also carry through the dark elements of the composition. She carries a ball with red, yellow, and green stripes. The ball is a simple device that connects the touches of beige and yellow, and the green landscape in the distance. Renoir kept this painting for the rest of his life.

The Renoir family moved in 1907 from Montmartre to Cagnes-sur-Mer, near the Mediterranean, to enable Renoir to take spa treatments and for better weather. Renoir tried sculpture as another outlet, but he never stopped painting no matter how disabled he became. He died in 1919. His last words were “I think I’m beginning to learn something about it.”

His painting and his family were his passion. He described his thoughts on his art: “The work of art must seize upon you, wrap you up in itself, carry you away. It is the means by which the artist conveys his passion; it is the current which he puts forth which sweeps you along in his passion.”

Happy Mother’s Day

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.