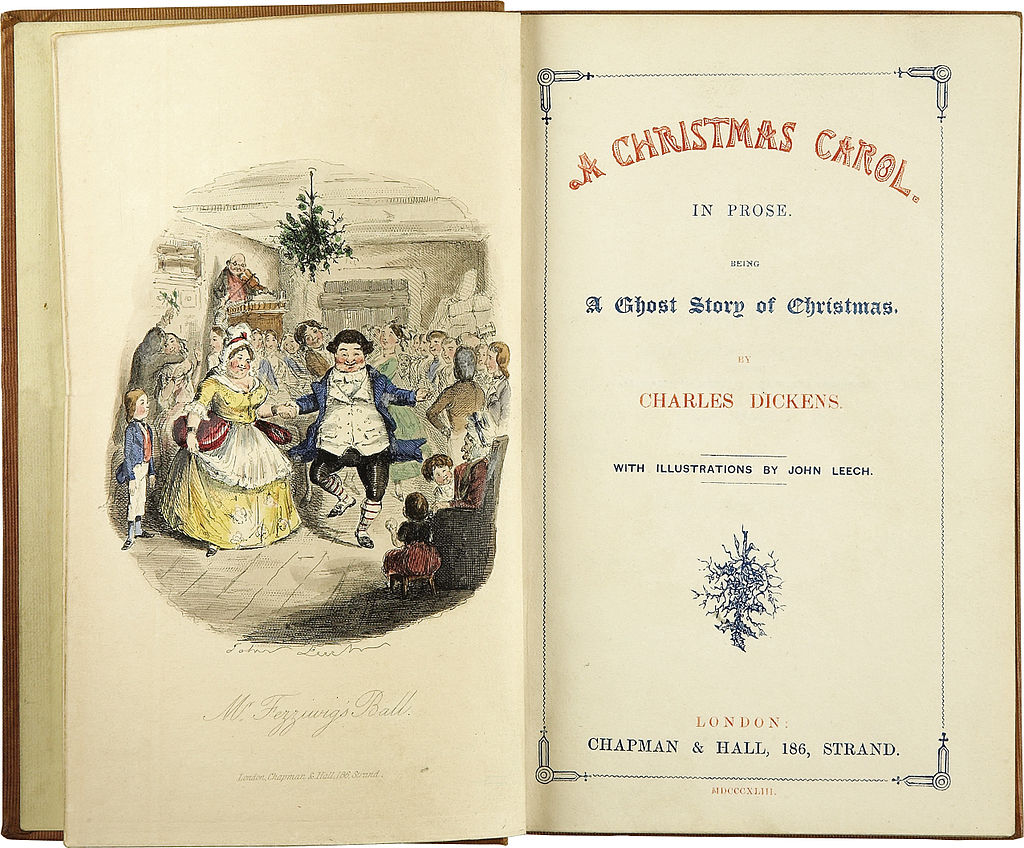

A Christmas Carol (1843) (title page of first edition)

Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol was published by Chapman and Hall in London in1843. The first illustrator John Leech created four hand-colored etched plates and four black and white wood engravings. His first illustration was “Mr. Fezziwig’s Ball” from Ebenezer Scrooge’s early life when he was in love and happy. By Christmas Eve, the first edition of 6000 books had sold out. Two new editions were sold out by the New Year. The story has never been out of print. The celebration of Christmas grew in popularity, and the Victorians developed new traditions.

Leech’s etching, the first appearance of the Ghost of Christmas Past, shows the jolly and rotund Mr. and Mrs. Fezziwig leading the dance. Fezziwig’s annual Christmas parties were famous. Known for his generosity and kindness, Fezziwig has provided a feast for all. A fiddler plays music from the balcony. Fezziwig’s elderly mother sits with some children and smiles at the joyous occasion. A young couple enjoy a kiss under the mistletoe. Holly hangs from the ceiling.

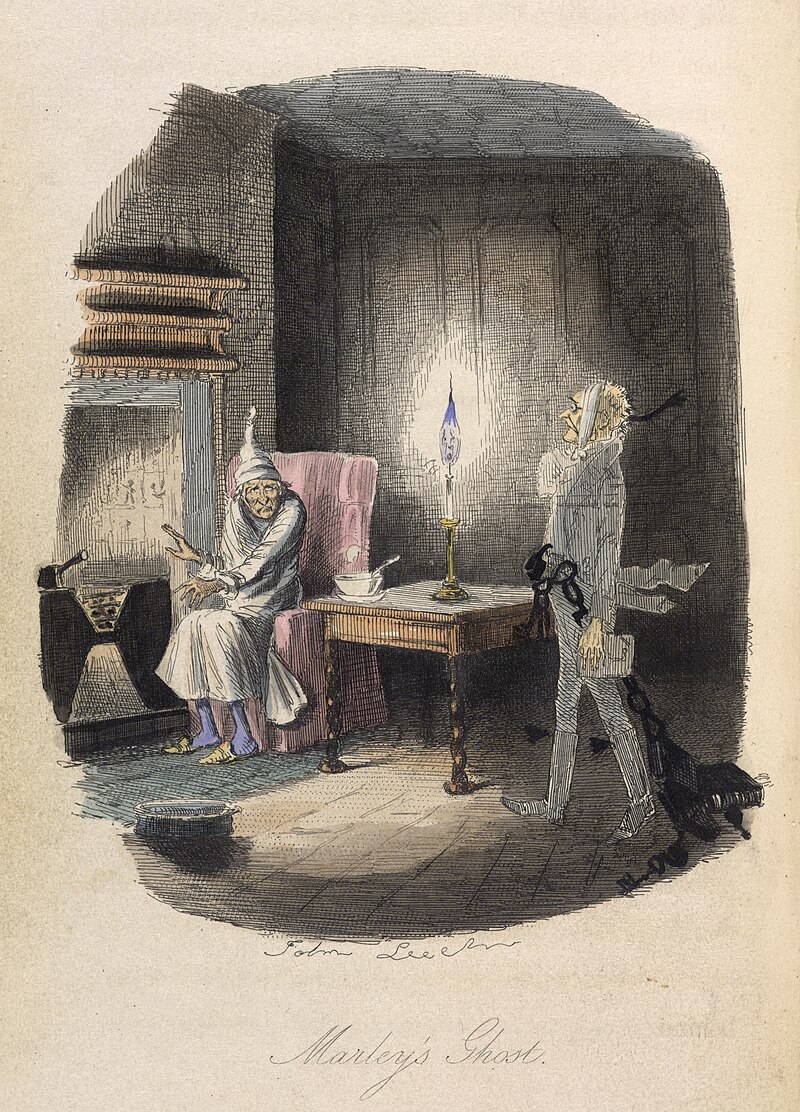

”Marley’s Ghost” (1843)

In “Marley’s Ghost” (1843), Scrooge’s former partner who has just died is an unexpected visitor on Christmas Eve. Dressed in his burial clothes, Marley drags chains and weights, the penance for his sins. Scrooge, in his nightclothes, sits near a small fire, eating a meager dinner. Only one candle lights the room. Leech has depicted the candle flame as a ghostly light. Marley warns Scrooge of the sins they both have committed in their business, and he forecasts the arrival of three spirits that will visit before Christmas Day. Scrooge must mend his cruel and miserly ways, or he will end up like Marley.

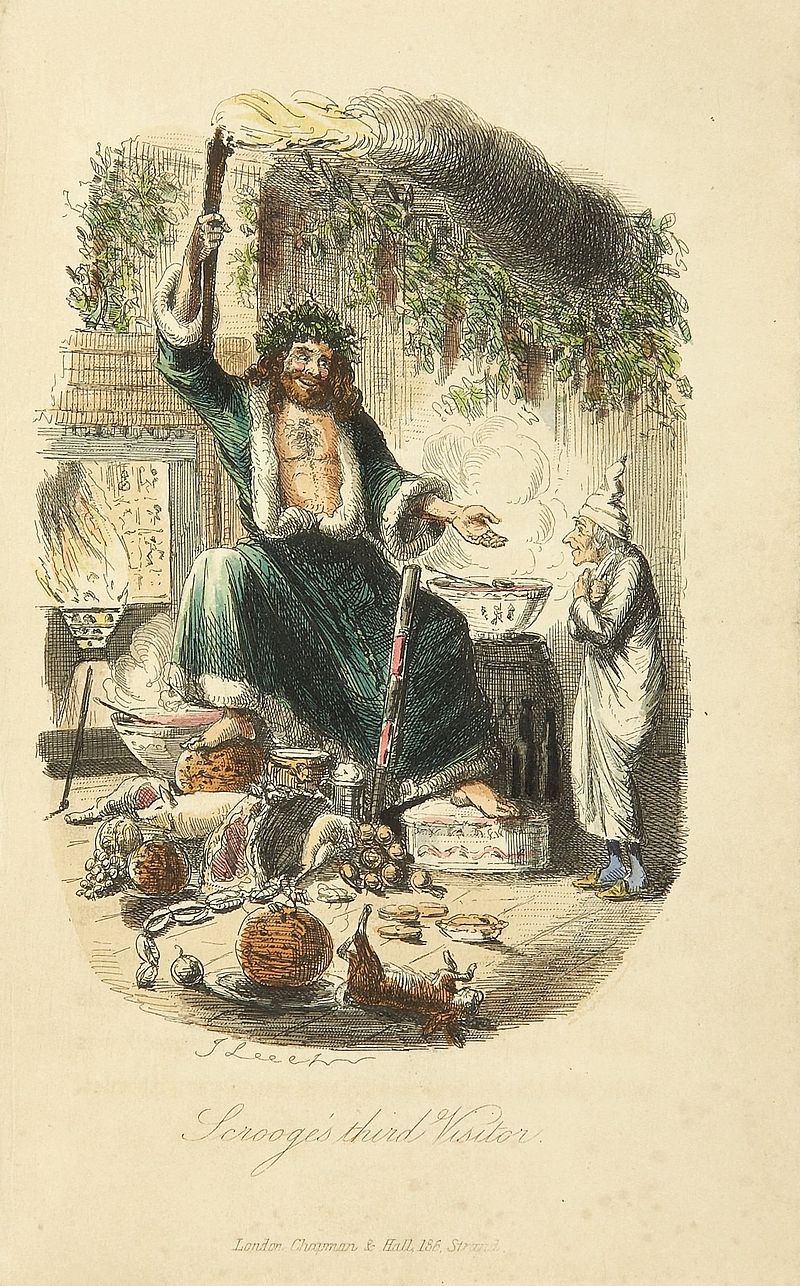

The Ghost of Christmas Present” (1843)

Leech draws upon the popular image of Father Christmas for “The Ghost of Christmas Present” (1843). He wears a dark green robe with white fur collar and sleeves. The room is filled with hanging greens. His torch and the fire provide light and warmth. His robe does not cover his chest, and his feet are bare. He wears a holly wreath decorated with mistletoe atop his curly brown hair. Around his throne are a rabbit, plum pudding, sausages, hams, and assorted other meats. He has a bowl of warm punch ready to share with Scrooge. He says to Scrooge, “Come in! Come in! and know me better, man.” He smiles, his eyes twinkle, and his voice is welcoming.

This image is one of the most popular in the story. The Spirit introduced Scrooge to another world. They first visit a flourishing market, where the rich are purchasing provisions for their feasts. The Spirit then takes Scrooge to a poor man’s house, and then to the home of his nephew, Fred. Every year the kindly nephew invites Scrooge to the party, but he never attends. They visit the home of Bob Cratchit, Scrooge’s poor clerk. Scrooge learns about tiny Tim and that he will not live long. The Ghost repeated Scrooge’s own words to him, “If he be like to die, he had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

“Ignorance and Want” (1843)

The theme of the woodcut “Ignorance and Want” (1843) was for Dickens a main element in A Christmas Carol. The Spirit shows Scrooge two starving, and poor children. Scrooge asks, “Spirit, are they yours?” “They are Man’s,” said the Spirit, looking down upon them. “And they cling to me, appealing from their fathers. This boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want. Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased. Deny it! Slander those who tell it ye! Admit it for your factious purposes, and make it worse. And bide the end!” “Have they no refuge or resources?” cried Scrooge. “Are there no prisons?” said the Spirit, turning on Scrooge for the last time with his own words. “Are there no workhouses?”

Dickens was born into the middle class. His father was a spend-thrift. He squandered the family money and was committed to debtor’s prison. Dickens was forced to sell everything. His interest in the poor was established as a result, and he visited several locations where children were forced to work in intolerable conditions. He intended A Christmas Carol to send a moral message and to expose the dire circumstances created by the Industrial Revolution. He wrote letters, gave speeches, and fought to address the deplorable conditions of children in as many ways as he found possible.

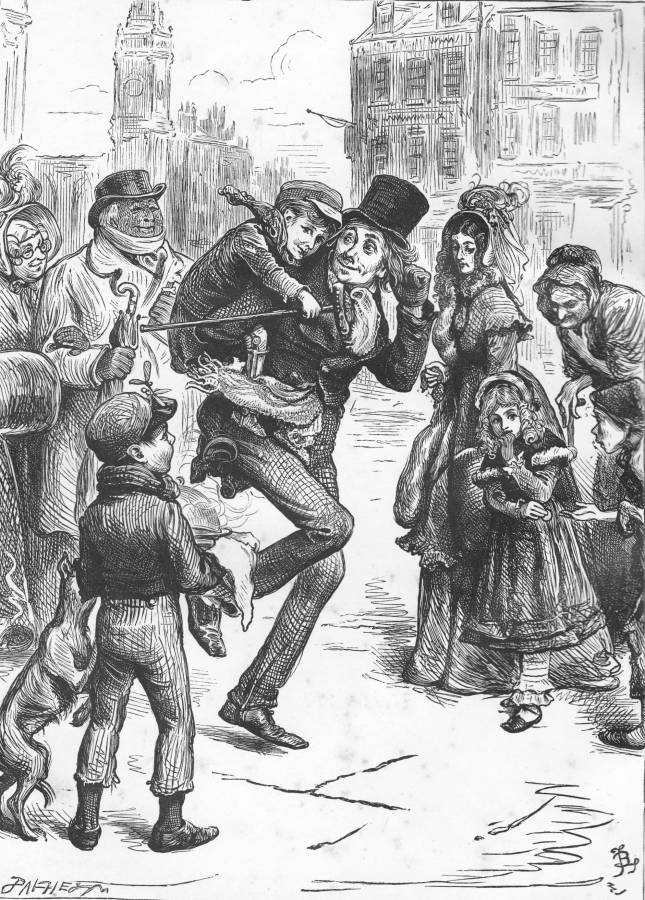

“Bob Cratchit and tiny Tim” (1878)

Dickens enlisted artists to create additional images for the early publications of A Christmas Carol. The black and white illustrations by Fred Barnard (1846-1896) are thought to be superior to the work by earlier artists. Barnard called himself the Charles Dickens among illustrators. “Bob Cratchit and tiny Tim” (1878) was another of the popular Dickens’s images. Bob Cratchit carried tiny Tim all over town, but particularly to church. His devotion to Tim was noted by everyone, young and old, rich and poor. A young boy with his dog delivers a large platter with the Christmas bird. A wealthy woman looks askance at the poor old woman. Her well-dressed daughter looks at an urchin who reaches out her hand. The young girl discretely hands the poor child a coin. The city of London is the backdrop. The distant clock tower resembles Big Ben.

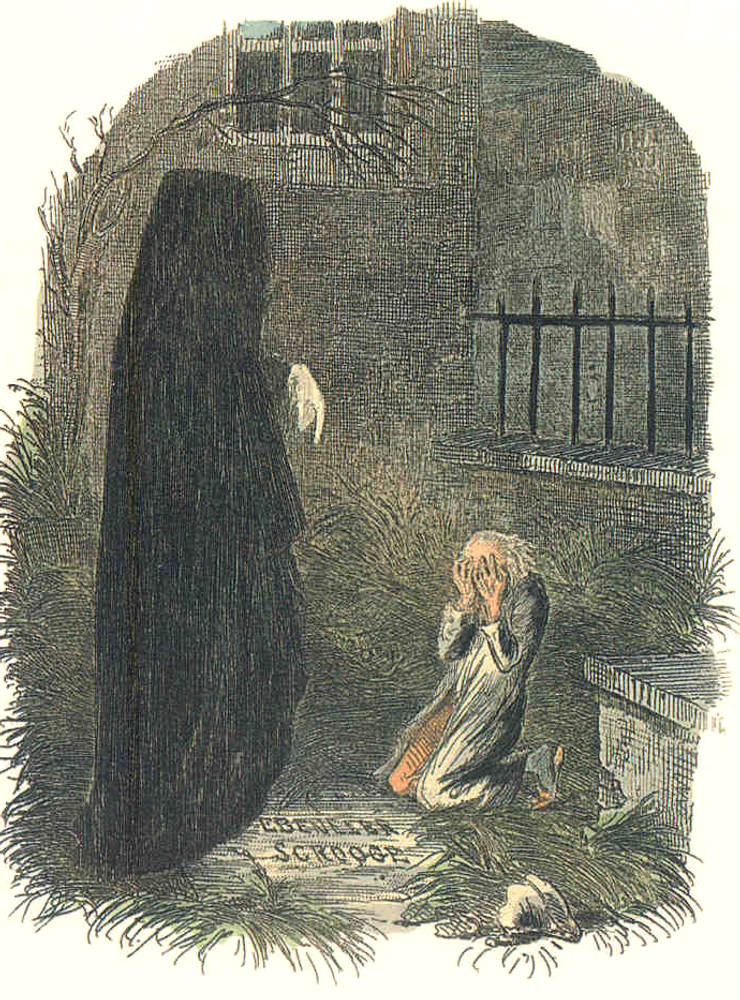

“The Last of the Spirits, The Pointing Finger” (1843)

In Leech’s “The Last of the Spirits, The Pointing Finger” (1843), the Spirit

of Christmas Present takes Scrooge to a graveyard. Scrooge implores, “Before I draw nearer to that stone to which you point, answer me one question. Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or they the shadows of things that May be, only?” The Ghost points downward to the grave. Scrooge responds, “Men’s courses will fore-shadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they may lead. But if the courses be departed from, the end will change. Say it is thus with what you will show me!” Dickens wrote, “Scrooge crept toward it, trembling as he went, and followed the finger, read upon the stone of neglected grave his own name. EBENEZER SCROOGE

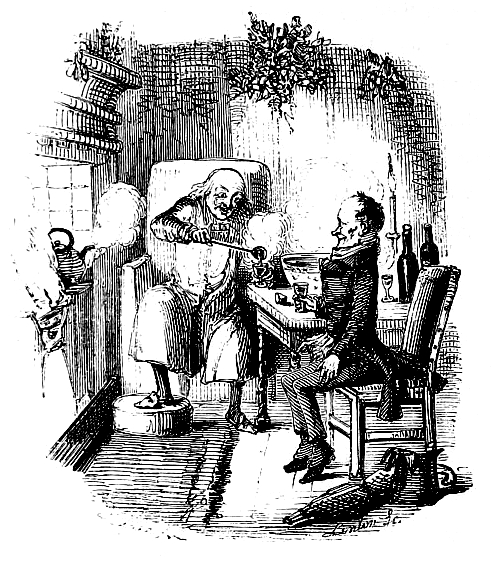

“Cratchit and the Christmas Bowl” (1843)

Leech’s illustration “Cratchit and the Christmas Bowl” (1843) presents a changed Scrooge. He shares a drink with Bob Cratchit. Dicken’s text reads: “A merry Christmas, Bob! said Scrooge, with an earnestness that could not be mistaken, as he clapped him on the back. A merrier Christmas, Bob, my good fellow, than I have given you for many a year! I’ll raise your salary, and endeavor to assist your struggling family, and we will discuss your affairs this very afternoon, over a Christmas bowl of smoking bishop, Bob! Make up the fires, and buy another coal-shuttle before you dot another i, Bob Cratchit!”

Have a Dickens of a Christmas

Note: Quotated material is drawn from Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol.

1 Samuel 7, during the end of the time of the judges, Israel experiences revival under the leadership of Samuel. The nation repents of their sin, destroys their idols, and begins to seek the Lord (1 Samuel 7:2–4). Samuel gathered the people at Mizpah where they confessed their sin, and Samuel offered a sacrifice on their behalf (verses 5–9). (1 Samuel 7:13–14). To commemorate the divine victory, “Samuel took a stone and set it up between Mizpah and Shen. He named it Ebenezer, saying, ‘Thus far the LORD has helped us’” (verse 12). Ebenezer means “stone of help.” From then on, every time an Israelite saw the stone erected by Samuel, he would have a tangible reminder of the Lord’s power and protection. The “stone of help” marked the spot where the enemy had been routed and God’s promise to bless His repentant people had been honored. The Lord had helped them, all the way to Ebenezer.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.