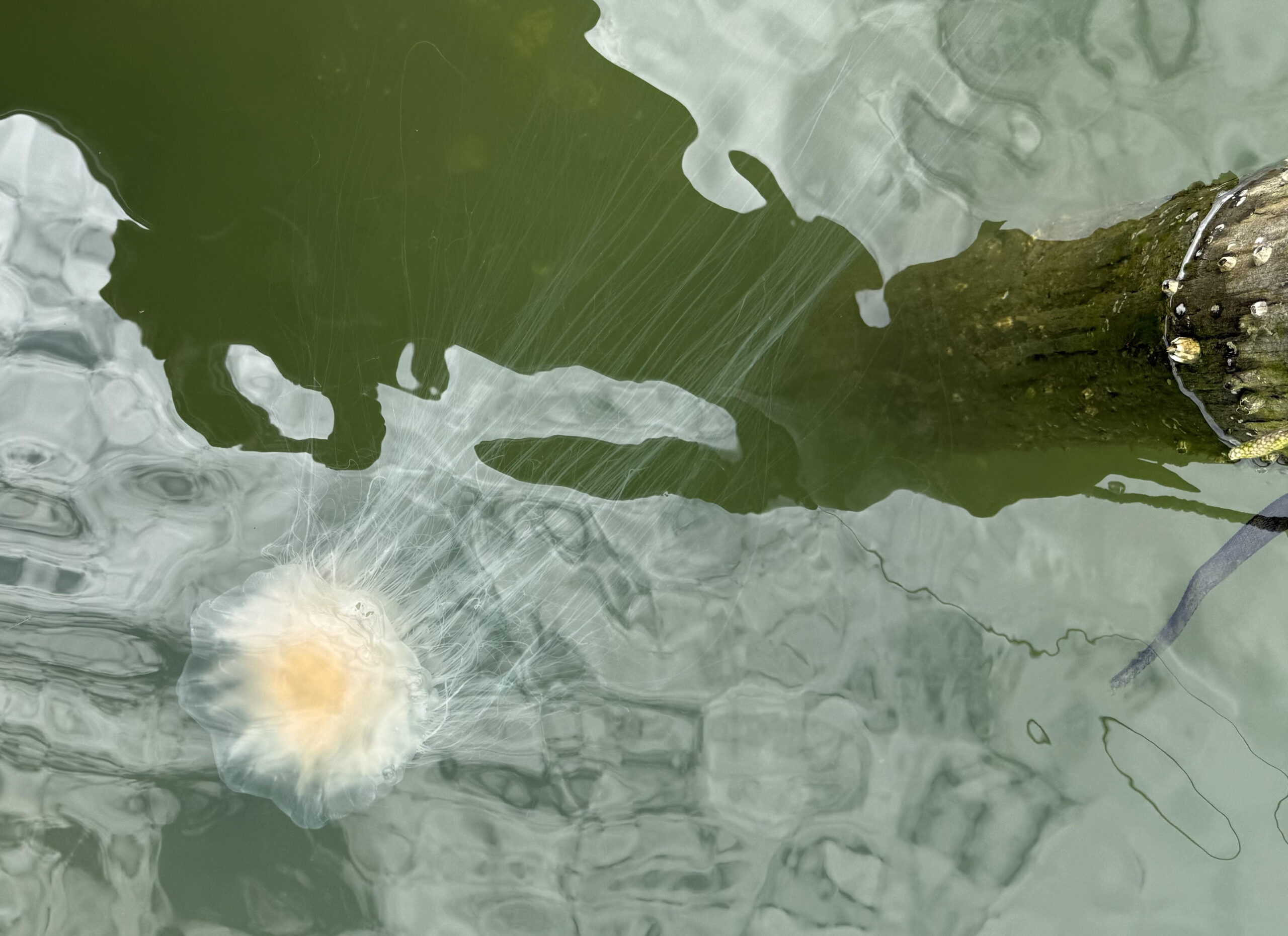

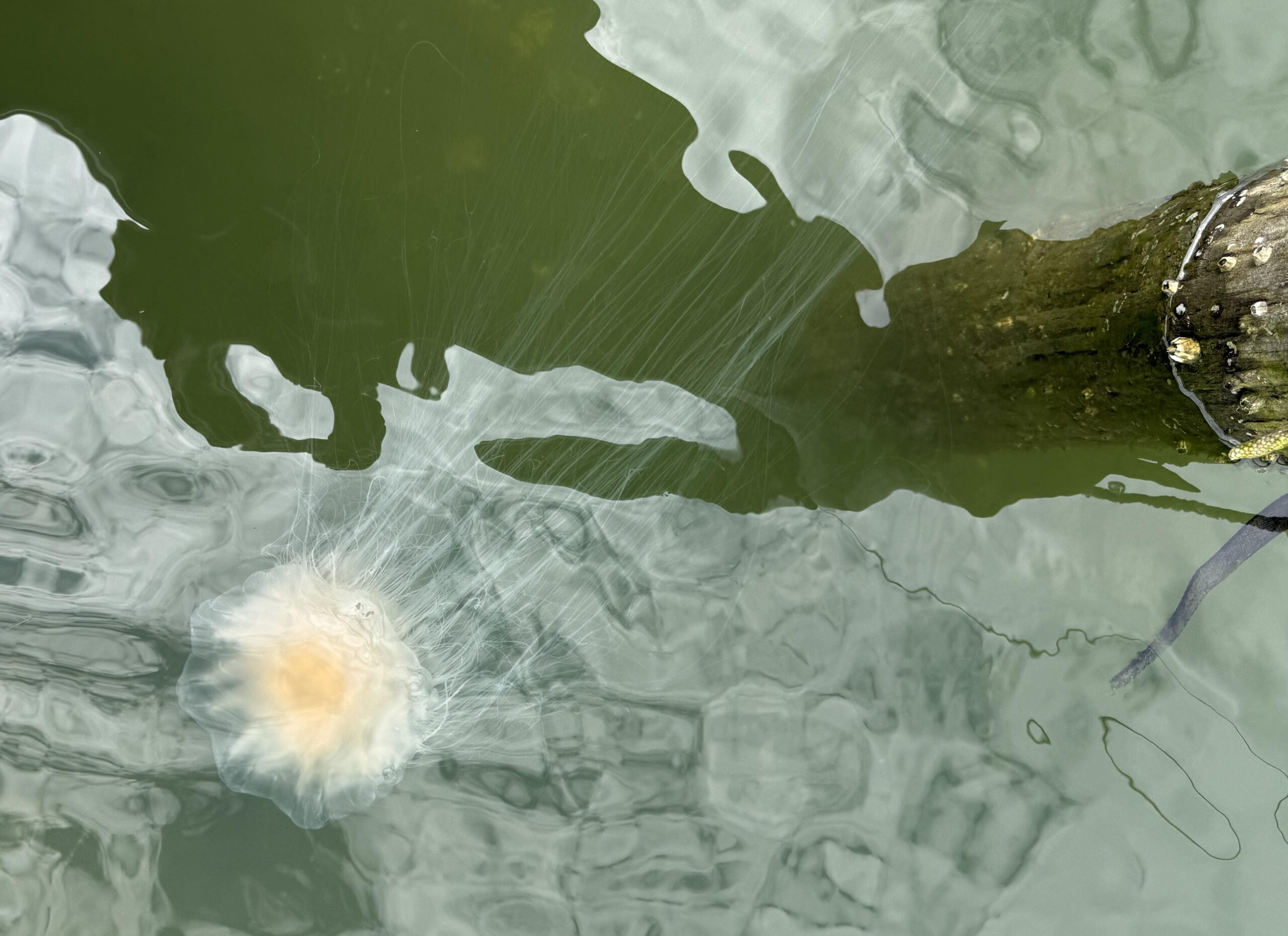

The large, orangish and red jellyfish floating around the surface of our creeks and rivers are another remnant of the cold winter quickly becoming a memory.

Lion’s Mane jellyfish typically inhabit colder waters of the North Atlantic but, drifting with currents associated with colder than usual temperatures, they can make it into the brackish waters of the Chesapeake.

According to articles posted by the Chesapeake Bay Program and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Lion’s Mane jellyfish are the largest jellyfish on the planet. A winter jellyfish, they can grow in the wide ocean of the North Atlantic as large as, and even larger, than blue whales. The size of their crowns has been measured up to six feet wide with tentacles greater than 100 feet long.

They show up in the Chesapeake, when conditions are right, in the late winter and early spring though they’re much smaller here than out in the ocean. Their sting is characterized as moderately painful, but are rarely reported because few people swim in local waters before they warm.

According to local watermen lore, the coloration has to do with their own version of spawning, after which they die and float to the bottom. There, the spent jellyfish are occasionally brought up on oyster tongs late in the wild harvest season, or like now, on the bottom-lying baits of trotlines just being deployed with the April start of the crabbing season.

Dennis Forney has been a publisher, journalist and columnist on the Delmarva Peninsula since 1972. He writes from his home on Grace Creek in Bozman.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.