Forty days and forty nights of utter chaos, half-truths and loud lies as clever operatives moved quietly and efficiently to seize computers, servers, and a staggering amount of classified data at federal agencies and departments. President Trump and his conniving partner Elon Musk, who has a whopping 40.5 billion dollars in federal contracts if you include the 2.5 billion Federal Aviation Administration contract he snagged last week from Verizon, and their zealots are running amuck inside government agencies to get deep inside federal programs funded by Congress. This is not a slick Hollywood screenplay. These bold intruders with government badges really did get inside federal systems loaded with rich information about you and me, and they gained access by commandeering Office of Personnel Management watchdogs who guided them into the sophisticated and little known data tool known as U.S. Digital Service. They pulled off this stunning heist in broad daylight without any legal authority, and few were watching. They had their targets and priorities at the ready, knew who was vulnerable, and in short order they closed down federal programs and fired thousands of targeted government employees who administered programs they deemed objectionable or unnecessary.

I suspect Musk and Trump view all this as a hostile takeover. Their lieutenants on the ground said they were DOGE and made clear their disdain for government workers. Let’s be clear. This massive takeover has only just begun.

The marauder in chief from South Africa gave Trump nearly 300 million dollars in campaign contributions and now he roams freely about the White House in black wearing a baseball cap. Musk has reasons to believe his 300 million gave him a personal mandate and undisputed authority to single-handedly create a new government with light or no regulation that reflects the Musk/Trump brand and ideals. This Musk brave new world enriches the most privileged and provides little for the needy. Transfer as much of the caring and feeding back to the states. Let them pay if they care. The president and his cronies won the election, but no one elected Trump and Musk to bypass Congress, ignore our laws, use technology to create a new federal government, and kiss Putin’s derriere.

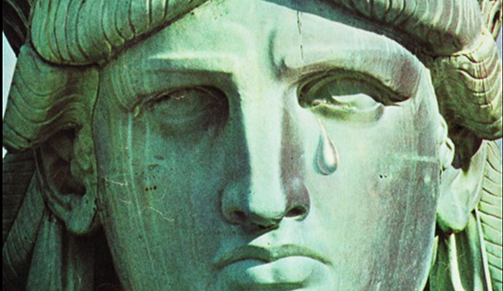

Instead of storming in with tanks, machine guns, and bayonets drawn this crew invoked DOGE Musk/Trump, flashed executive orders, and were quickly inside government networks and systems and had a staggering amount of classified data. Afterwards they escorted their stunned targets out of the buildings. Call it a hostile takeover if you like. To me it feels more like a coup d’etat underway “O’er the land of the free and home of the brave.”

A spineless Republican Congress cowers on the sidelines pretending nothing out of the ordinary is going on even as they are being neutered and rendered useless. Congressional Democrats appear paralyzed, unable to explain to the American people the danger going on. Notwithstanding a few brave souls calling the cowardly Trump out, most Americans, including lawyers and their state bar associations, teachers, doctors, bus drivers, nurses, students and professors, the baristas and bartenders, clerks and brokers, and members of the clergy, remain stunned and mostly silent.

None of this happened in a vacuum. Trump’s maddening chaos and distractions at home are directly linked to several of his campaign promises, including ending the war in Ukraine quickly. For years Trump told us Putin wasn’t such a bad fellow, that he could do a beautiful deal with Putin, foreshadowing the post WWII transatlantic alliance of America cooperating and partnering with its European partners was on life support. Trump invariably added NATO and our European Union trading partners were taking advantage of our generosity and competing with us unfairly.

Trump calculates, rightly, I think, he must deliver MAGA and his Christian right a few big wins and do it quickly before the tide turns against him, before we learn how much he is doing for Russia. Therefore, he and Musk are hell-bent on deregulating government without going through Congress. They are out to cut trillions in federal spending so the richest Americans can pocket trillions in another huge tax cut, no matter the costs to the poorest. And they want this cut permanent. Next, quickly rid America of millions of undesirable black and brown immigrants at breakneck speed without going through Congress. Forget the rule of law, human suffering, and deaths. Kick immigrants out now or hide them on secured military bases like Fort Bliss, Texas, and send more service members to the border to be policemen, a role for which they are not trained. Quick deliverables paramount. Break the Limoges and as many people as needed to get those wins.

Kill DEI throughout America. The first executive order issued focused on the Defense Department, targeting transgender service members who have served successfully for years. In Trump’s world these patriots pose a major threat and must be gone in thirty days, fire the female head of the Coast Guard immediately, fire women and blacks in leadership roles who must have been diversity picks and are clearly a threat to unit cohesion, good order, discipline, and morale, and, lastly, drum out the top JAG lawyers who serve the constitution first, not a president’s whims and wishes.

And along comes Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky to the White House last Friday afternoon with hat in hand, but soon it’s clear Zelensky is not entirely with the Trump program and priorities. Zelensky doesn’t seem to appreciate President Trump promised to end the war in days, that Trump needs his big win in Ukraine and soon. As President Trump and his shameless oval office band of sycophants saw it last Friday their rude visitor even had the temerity to be thinking long term, to be concerned about the future security and safety of his people, that the visitor didn’t trust Putin to keep the peace and his promises!

The “ingrate” from Ukraine, as Trump’s devoted gang viewed matters, didn’t appreciate President Trump had his own pressing needs at home, that the president planned to tell his Congress in his State of the Union address Tuesday night that victory in Ukraine was near, that his beautiful deal would save the world. Surely Zelensky had seen Trump’s USA, along with North Korea and China, voting at the United Nations with Russia on the war in Ukraine.

And here was this Zelensky talking back to the president, insisting it was Putin who invaded his county, not the other way around. That was enough to send this White House over the top. Millions around the world saw Trump, and America, in real time. Just you wait, Zelensky, the White House threatened. You have no cards. We’re about to show you how much President Trump can favor Russia, maybe even normalize U.S. relationships with Russia. Don’t be shocked when we stop funding and weapons to Ukraine. Our compliant Pete Hegseth may stop pentagon cyber operations against Russia. Who knows, but Putin knows how to say thank you. Think these are negotiating tactics to have you crawling back? Europe will save you? Don’t be so sure.

This American was disgusted and ashamed by what he saw televised from the oval office last week. Our president who never wore the uniform of our country and who invariably thinks me, myself, and I ganged up with his White House staff to disrespect a brave man who has waged a long, deadly war for freedom against an invading brutal dictator. As if that sad spectacle wasn’t bad enough, clueless Congressional Republican toadies and Neville Chamberlain appeasers rushed in to attack Zelensky and side with Putin. As New England lawyer Joseph Welch put it to Senator Joe McCarthy in 1954, “Have you no sense of decency, sir?”

None of us knows where Trump’s tantrums and threats on tariffs, his irrational attacks on Ukraine, and his flirting with switching sides in the middle of the Ukraine War may be going. All of this is very frightening. I hope some members of the House and Senate stand up on the floor of the House of Representatives Tuesday evening and turn their backs when President Trump attempts to justify why he licked Putin’s boots in the White House Friday, attacked Ukraine’s brave leader, threatened to switch sides in this war, and declared our European allies don’t matter to him anymore, that our transatlantic alliance is over as far as he is concerned.

Aubrey Sarvis served as a senior Senate and House staffer, and Director of Servicemembers Legal Defense Network (SLDN).

The iridescent blue wings of the male Blue Morpho butterflies have long fascinated people and scientists. The Blue Morpho does not use pigment to create its bright blue iridescent color on its wings. Rather than absorb and reflect certain light wavelengths as pigments and dyes do, their wings have a layered microstructure that causes light waves to hit the surface of the wing to diffract and interfere with each other so that certain color wavelengths cancel out while others, such as blue, are intensified and reflected. The Morpho’s colors are a structural color, reflecting only blue light due to the wings’ unique nanostructure. At the University of Rochester, researchers are studying this phenomenon to develop light-absorbing materials for solar panels. By mimicking the Morpho butterfly’s nanostructure, they can create an absolute black which will increase solar panel efficiency by 130%.

The iridescent blue wings of the male Blue Morpho butterflies have long fascinated people and scientists. The Blue Morpho does not use pigment to create its bright blue iridescent color on its wings. Rather than absorb and reflect certain light wavelengths as pigments and dyes do, their wings have a layered microstructure that causes light waves to hit the surface of the wing to diffract and interfere with each other so that certain color wavelengths cancel out while others, such as blue, are intensified and reflected. The Morpho’s colors are a structural color, reflecting only blue light due to the wings’ unique nanostructure. At the University of Rochester, researchers are studying this phenomenon to develop light-absorbing materials for solar panels. By mimicking the Morpho butterfly’s nanostructure, they can create an absolute black which will increase solar panel efficiency by 130%.